In the US, cantaloupes, pine nuts, romaine lettuce and sprouts caused serious outbreaks of illness in 2011, according to a recent report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

In fact, five of the most significant or unusual outbreaks of foodborne illness involved fresh produce. The CDC said that 2011 was the most active year in recent history for ‘foodborne illness outbreaks that crossed state lines’.

The health-related cost of foodborne illness in the US is $77.7 billion, according to a new study - Economic Burden from Health Losses Due to Foodborne Illness in the United States – published in the Journal of Food Protection (JFP).

That’s approximately half of the widely quoted $152 billion cost calculated in 2010, but it’s not necessarily due to improved food safety. The JFP study bases these new numbers on the CDC’s latest estimate that 48 million cases of foodborne illness with 3,000 deaths annually occur each year. Those numbers were revised down from the 1999 CDC estimate of 76 million cases with 5,000 deaths each year.

The author of the report, Dr. Robert L. Scharff of Ohio State University, cautioned that:

‘Total cost figures are useful as measures of the scope of the problem, but the numbers do not by themselves provide economic justification for any particular program aimed at reducing foodborne illness.’

Even though it often grabs the most headlines, E. coli doesn’t account for the majority of the health-related cost of foodborne illness. The O157:H7 strain’s infections were estimated at $635 million a year, and non-O157 strains of Shiga toxin–producing E. coli added another $154 million.

The top three costliest bugs are Salmonella ($11.39 billion cost in illness per year), Campylobacter ($6.88 billion) and norovirus, which tends to occur in foodservice settings, (3.68 billion). Also of note, Toxoplasma gondii, a parasite that might be present in uncooked or undercooked meats, cost $3.46 billion. Lastly, Listeria monocytogenes resulted $2.04 billion in sickness related costs.

Importantly, this analysis includes costs for medical care, productivity losses, deaths, pain, suffering and functional disability, but not any long-term resulting health effects. Nor does it include the price paid by the food or foodservice industries to issue a recall, dispose of product and/or clean up their act, or public health agencies that have to investigate the outbreaks. Or the resultant PR campaign to restore a company’s reputation, if indeed it is salvageable. And it certainly does not monitor the after-effects that a major crisis can have on sales or even a whole industry.

For example, the 2011 Listeria outbreak in cantaloupe melons in Colorado that caused 30 deaths reduced US cantaloupe consumption by 53%, according to one consulting firm, Perishables Group. The fact that most cantaloupe are not even grown in Colorado, but in California and Arizona, was inconsequential. Consumer perception, after all, is everything.

To emphasise the critical nature of food safety, in December 2011 officials released The Federal Food Safety Working Group Progress Report. Coming one year after the implementation of the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), the report outlined its ‘2011-12 Agenda and Beyond’, which includes a focus on pre-harvest food safety, preventive control standards, retail food safety, modernised food-safety inspections and safety of imported products. Among the steps announced are a zero-tolerance policy for six additional strains of Shiga toxin-producing E. coli in 2012, and a new ‘test and hold’ policy.

Over in the UK the picture is somewhat different. The most recent foodborne outbreak epidemiological data is available via Public Health England (PHE) charting instances from 1992 to 2010. Although the figures are not directly comparable, according to the PHE, poultry meat was the most frequently implicated vehicle in food outbreaks in England and Wales during this period; a much smaller proportion was associated with fresh produce and a range of other foods.

While produce may not be top of the list when people think of ‘danger’ foods, this doesn’t mean we can stop being careful. Last year’s E.coli outbreak in Germany was due to sprouted fenugreek seeds, and there was a separate E.coli outbreak in the UK linked to handling certain loose raw vegetables. The range of culprits that caused outbreaks in the US shows how foods you might not suspect can be the source of serious illness.

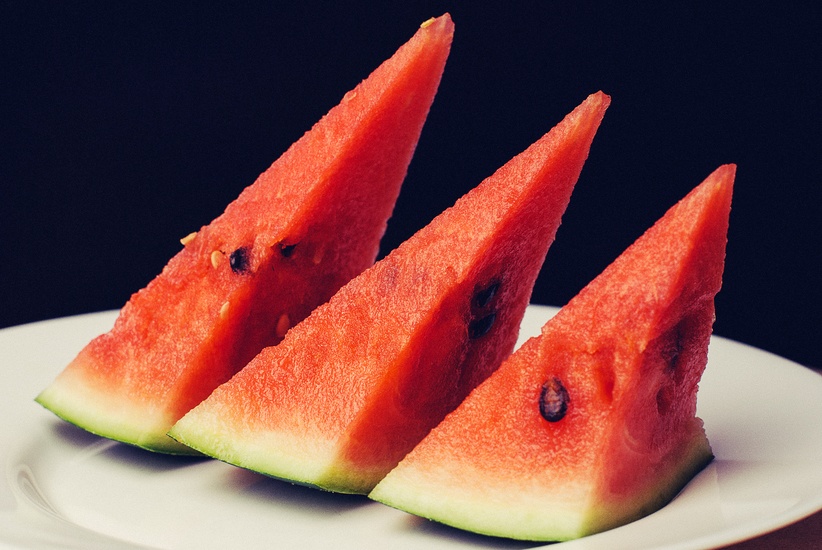

To raise awareness of the importance of good food hygiene, the UK Food Standards Agency (FSA) ran a media campaign in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland reminding everyone to wash vegetables, as well as their hands and any utensils used in preparation.

The campaign has recently finished, but the FSA’s message remains the same – ‘Vegetables: best served washed.’

(Image Credit: tookapic via www.pexels.com)